PRESS

ARTIST RESIDENCIES: HOW CHANGING PLACE CHANGES WORK. Tuesday December 4 2012

Deanne Butterworth

“There is something about working away from where I live that enables me to focus quite differently and more intensively to how I might usually work during a period of development. Away from my usual place of residence I cannot sink into regular patterns, clinging onto familiar relationships with places or other people, my favourite coffee and other distractions. I have to be completely present to the situation, which is both new and strangely familiar. New relationships start to develop with people I know well, different configurations and patterns emerge and other characteristics of colleagues become apparent that I would not usually have the chance to know. Finding time alone takes on some precedence and this becomes a sort of reflection time for the intensive working process. The work never escapes from me. ”

for the full article go to ARTS HUB

dual repérage in threes for Dance Massive by Keith Gallasch

“Butterworth’s Dual Repérage in Threes works the length of the venue’s upstairs Studio. To our far right, the choreographer-dancer appears abruptly, in a flurry of extensions, silhouetted in front of a human scale rectangle of bright, softly coloured light. Butterworth’s relationship to this light source is pivotal: she constantly moves away from it to the centre of her stage, sometimes further, only to return to it, sometimes moving backwards into its acute frame. The dancer is not miming push and pull, but the magnetism is evident—sometimes in a mere walk, sometimes as if she’s danced by an unseen force. As if to amplify the work’s anxious, moth-to-a-flame vibrancy, a hand-held torch lightly tracks Butterworth, casting a flickering shadow on the long wall as she moves into the dark.

Michael Munson’s score resonates with the dance; initially short, deep chords and high piano twangs suggest the solidity of acoustic sources, providing a palpable physical sonic pattern against which the dancer’s restive body moves regardless.

As Dual Repérage in Threes evolves, Butterworth’s choreography takes shape, cumulatively building on a calculatedly limited set of movements with occasional, strikingly different images (sculpted posturing, balletic tip-toeing, feet ‘stuttering,’ rapid pelvic thrusts) breaking the routine. The dancing’s not minimalist as in, say, some Molissa Fenley works, but the recurrence and recombination of motifs can be hypnotic or, at times, hard to hold together. Arms lead the body in wide turns, swing over shoulders singly and then together, back and forth at speed; hands spin rapidly over each other; and, in a dominant image, the dancer’s upper body is constantly pulled down towards the floor, centrestage, hands reaching, half-cupped as if something sighted is beyond grasp—the strange potency of this gesture is heightened by the addition of a percussive element to the sound score.

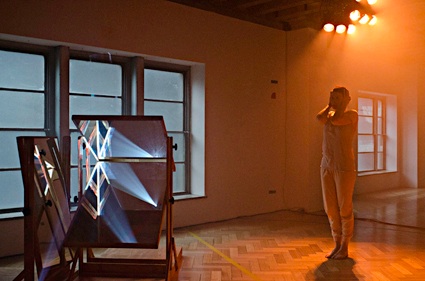

Deanne Butterworth, Dual Repérage in Threes

photo Rohan Young

The work is played out in two sections—there is a ‘private’ third that only Butterworth experiences or we can imagine, as she suggests in her opaque program notes. As the first ‘act’ progresses, the pull of the light is amplified when it turns slowly, softly orange, Butterworth travelling elegantly sideways, then walking serenely towards it. On arrival, she oscillates between bursts of energy and calm, drifts back to the centre, again as if seeing...what? Sweet organ-like tones fill the space. Black-out. Butterworth stands over a flickering fluorescent light as she commences her second ‘act,’ in which the rectangle of light is a vivid orange, and the images into which she recurrently locks are more intense, more urgent while others—like squared-off poses, moments of rare stability—are added. A thin line of lilac light illuminates the space where wall and floor meet, drawing a crawling Butterworth away from her principal light source, perhaps into some kind of release. In a moment that seems to break even further from the work’s patterning, Butterworth is no longer compelled to bend low; instead she clenches a fist and reaches out directly to us. It’s a powerful almost implicating moment, if again an abstract one.

In the work’s climactic moments, Butterworth returns to the light, a deep musical pulse underlining a frightening escalation of the work’s key motifs—arms and hands spinning, body pulled down and forward over and over. I’m not sure precisely what I witnessed in Dual Repérage in Threes, but Deanne Butterworth’s adroit coding of her choreography (inflected with years of dance know—how, superb balance and rapid gear-shifting) and the work’s near obsessive—compulsive realisation made for a compelling experience.”

for the full article go to REAL TIME #102

twinships at west space

metaphors, binaries & mergings by Varia Karipoff

Deanne Butterworth, Twinships

photo Rohan Young

“DEANNE BUTTERWORTH’S TWINSHIPS IS A HYBRID CREATURE THAT MELDS DANCE WITH INSTALLATION, WITH A DOSE OF WELL-CURATED SOUND RECORDINGS FOR GOOD MEASURE. THE INSTALLATION COMPONENT CONSISTS OF COLOURED LINES MARKING OUT THE PARQUET FLOOR. WE COULD BE INSIDE A SPORTS HALL; A CURVED LINE RESEMBLES THE THREE-POINT ARC OF A BASKETBALL COURT.

Three mirrors are joined together in a frame contraption and are set at different angles to reflect projections across two walls, a sliver of a triangle on one wall and a bigger slice of moving image on the back wall. Themes of nature, emotional states and a final video of a streetscape through a window create a mood background for the dance.

When we enter Westspace, a smoke haze fills the room. Amid the sound of cicadas and wind blowing, a large paper scroll is unfurled by assistants. A dancer soon appears behind it. Butterworth’s figure casts shadows across the paper and, as she moves alongside it, she briefly seems to be painting. As in Japanese calligraphic art, her body becomes the honshi, the centrepiece artwork. Bending down and bringing her arms down to the ground, Butterworth’s silhouette becomes an inky mountain. From my angle her feet, which are visible beneath the scroll, are about two inches left of her shadow. While her body is graceful on paper with balletic control, her exposed feet with quivering tendons, show the effort in such grace.

The projections cast on the wall via the mirrors provide mood cues during the performance. While interesting sculpturally, the mirrors themselves have only a subtle effect on the projection and their presence is quickly forgotten. There are five chapters to this dance that the projections help to define by colour. In the second part of the dance, red dominates the projection as Butterworth moves like a boxer, swaying and shifting her weight from foot to foot. Repetition and her stance evoke sports training or a controlled fight. Meanwhile the projected video footage becomes choppy—a red sky with scratching tree branches has a schlocky horror film look. The red gives way to green and a recording of a science lecture plays, signalling a return to rationality and control. Butterworth repeats the same step-by-step movements on the spot, tense arms folding and reaching forward as though she is practicing her moves. She then turns on the spot like a cog. Her arms chop the air like windmills before she dissolves into more fluid movements, also reflected in the projection with a close up of tidal waters.”

for the full article go to REAL TIME #112

TWINSHIPS Review by Andrew Fuhrmann for TIME OUT MELBOURNE 6th November 2012

“In a sense, dancers and performance artists generally are in peculiar state of tension with the idea of twinship. The classic image of this is the dancer practicing at bar before a full-length mirror. The dancer has in mind an idea of the dance – the dance as it should be. But then there is a second dance, that of the double in the mirror, the dance as it is. The impossible challenge for the young balletist is to bring these two into a single identity, to cross the shadow between what might and what is.”....

.....“The multiple twins here have many faces – illuminated and shadowed, projected and reflected, native and civilised – faces which are looking, like everybody else, for the limits of separation and alienation, for the point where the repetition of small infringements gives rise at last to something substantial, something new, something more than a mere reflection. In the final moments, beneath a bank of warm orange lights and amid a chorus of bird calls and jangling piano strings, Butterworth's movements are almost mimetic, suggesting growth and fruition, like seedlings shooting beneath a mellow sun – a hopeful note on which to end.”.....

for the full article go to TIME OUT MELBOURNE

DANCE CARD, DANCEHOUSE 2004 by Jonathan Marshall

...“Alongside these promising explorations from relative newcomers sat Deanne Butterworth’s wonderful, effortlessly massive performance. Frequently featured in projects from Dance Works and Shelley Lasica, Butterworth is a master of seductive lyricism. For all the elegant beauty of the choreographic palette she has enjoyed, there is nevertheless a danger that she might simply echo that highly attractive, sparse lyricism in her own work. By dressing herself in what appeared to be a gorilla suit without a head, Butterworth undercut expectations. Floppy ripples of black fur drew attention to the dance’s focus on unforced manipulations of weight through the hips. The fur also highlighted the lethargic beauty of Butterworth’s softly moving form, as she gently released into the ground and then lightly returned to stand using only a few well-chosen, yet unassuming movements. It was the gentle undulation of hairy cloth and inertia that gave this work its ambiguous drama.”

for the full article go to REAL TIME #60

WATERMARKED I, Published 1st May 1995 The Age, by Robin Grove

... “The question is, how does the term apply here? Imagination, it appears, is less than reality, but greater than it too. Which is the original, which the copy? I enjoyed being made to look twice, this way. And looking twice is the pattern of the piece. It's not just that individual sequences are repeated, but that familiar features can be inspected anew. Under the steady pressure of Butterworth and Richardson's performance, a plie seems doubly deep, a backwards fall as slow as the topple of a felled tree. When a small jump occurred, it looked far larger than it was, so used had we become to the grounded, gravitational quality of their dance.Most ``abstract" dance is about human experience at one remove; this was about living, feeling, thinking, at three or four distances from the fact witness the unengaged hands, used not to stroke and reach and clasp, but to complete a sculptural form. If an arm is stretched out, the hand merely extends it, adding no expressiveness of its own; if the head rests, it is on the back of the hand, not the palm, since the sensitive centre inside the fingers forms no part of the choreography. Beautiful but impassive, the hands duplicate the composure of the faces, sphinx-like in Butterworth's case, more eager, only intermittently veiled in Richardson's.

This remoteness gives a curious authority to the work, an undramatic, dream-logged preoccupation, as if everything that might be discovered about space is as yet untouched, waiting to be found for the first time.

One might wonder how much Watermarked I does finally bring back from the deep, but it is a considerable achievement to look as pristine as this in the anxious, self-conscious 1990s.”

for the full article go to THE AGE ARCHIVE